Perfection in Proportions

I’ve always known which cars make my pulse jump and which ones leave me cold, but it wasn’t until I started measuring proportions that I understood why. Once you put a few simple ratios on a side profile, the mystery fades: some designs respect the human eye, and some ask for forgiveness. To make this tangible, let’s compare a stone-cold classic, the BMW E46 M3, with a modern sales phenomenon, the Tesla Model Y. Both are capable machines. Only one looks inherently athletic at a glance.

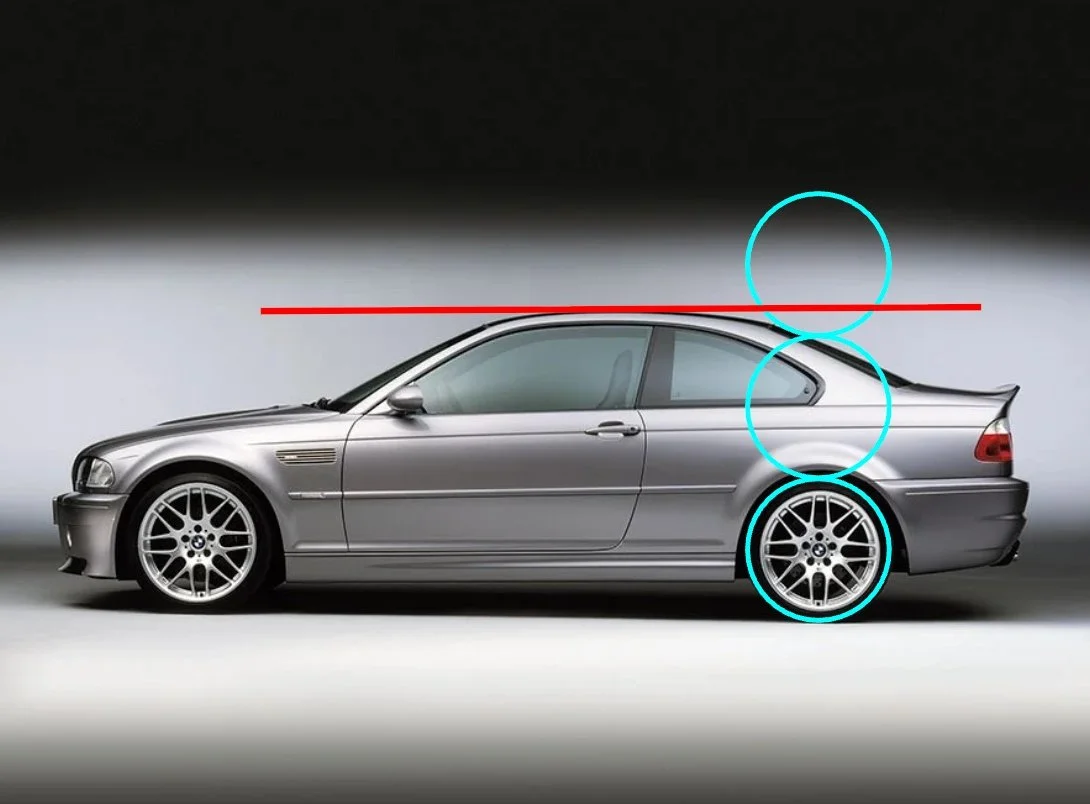

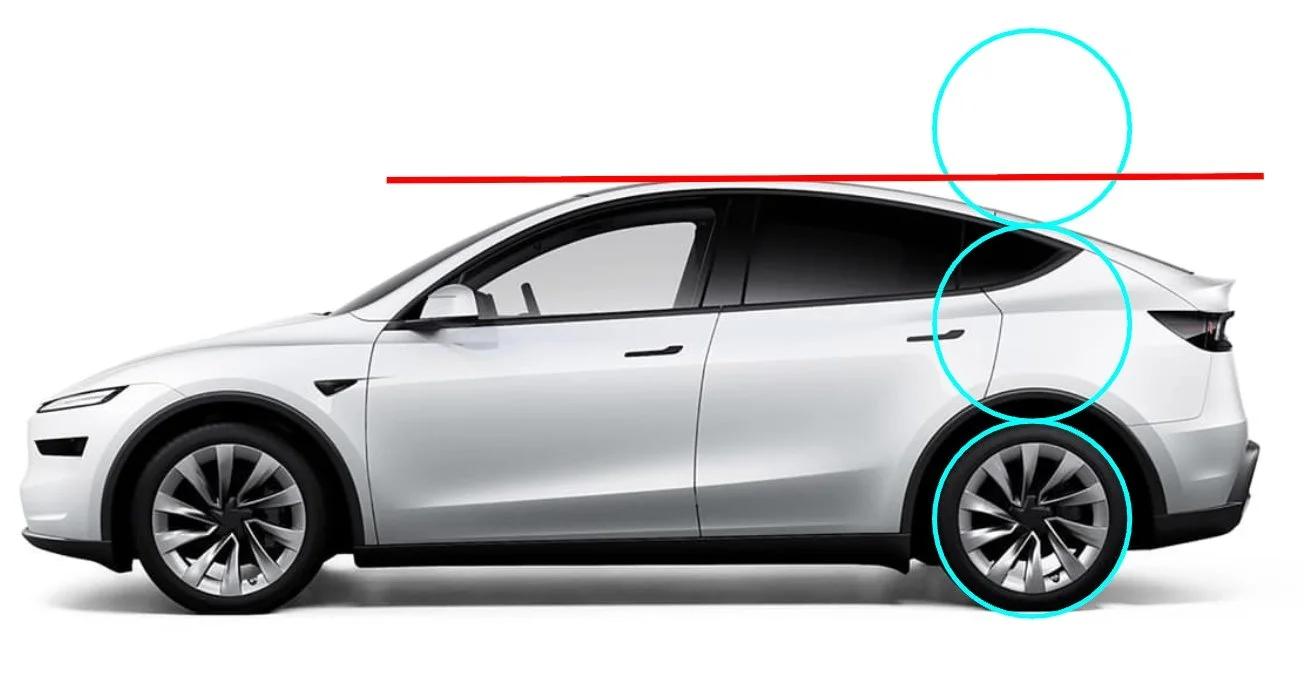

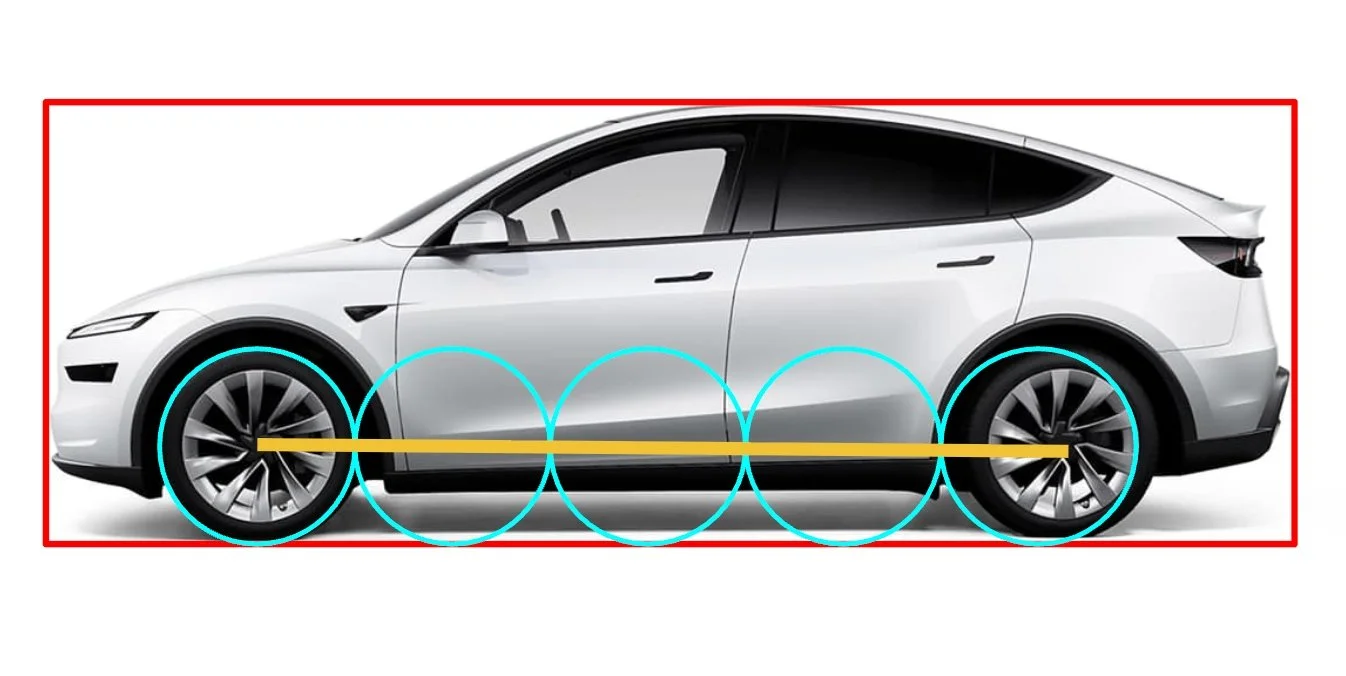

1) Height vs. Wheel: the fastest tell

Use this ratio first because your brain uses it first. Take overall height and divide by tire diameter (not rim size).

E46 M3: overall height ~1,38 m; typical tire diameter ~0,66 m → ~2.08×

Model Y: overall height ~1,63 m; typical tire diameter ~0,71 m → ~2.28×

Lower is sportier. Around 2.1x - 2.4x feels planted for coupes/GTs; 2.6x - 3.0x is common in crossovers. The Y isn’t cartoonish, but it’s clearly taller per unit of wheel, so the body reads heavier even before you clock anything else. This is why upsized wheels rarely “fix” a tall crossover: the body is still winning the vertical argument.

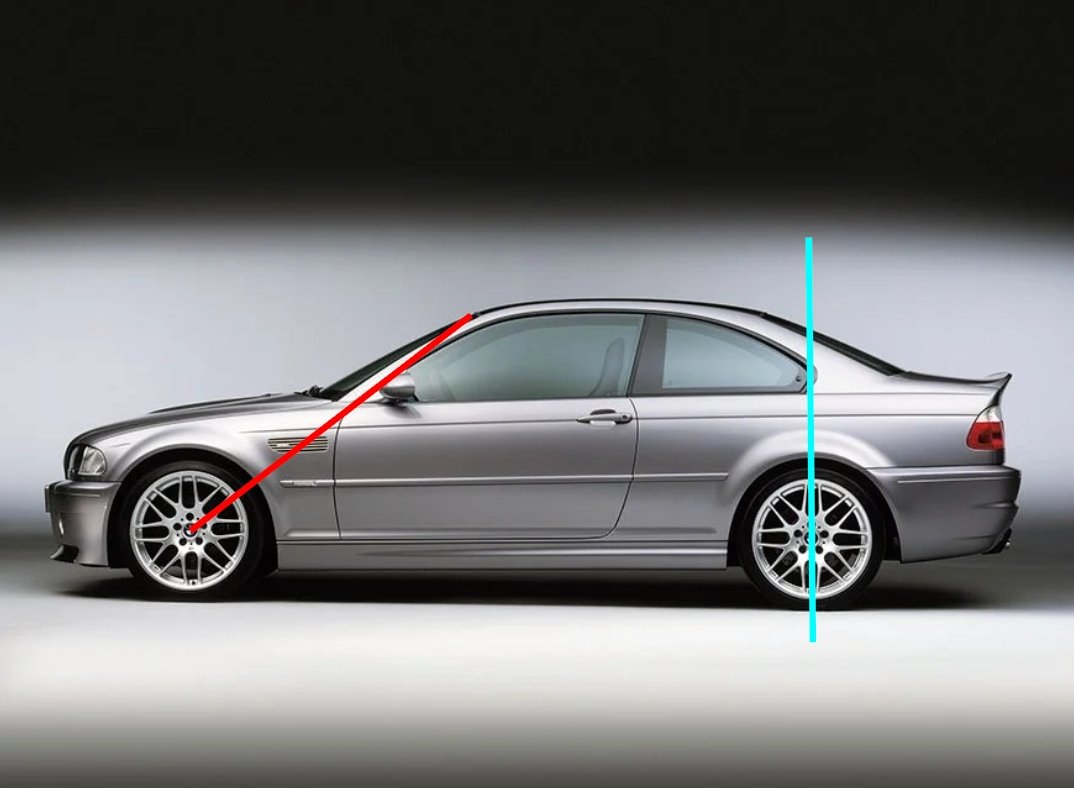

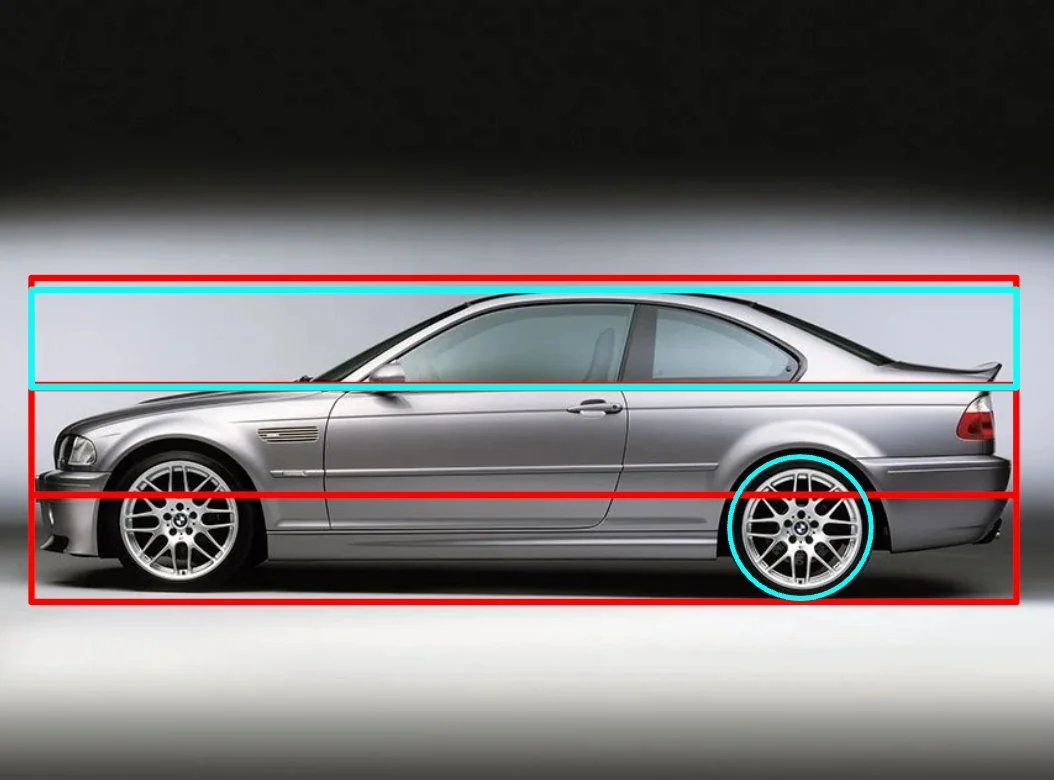

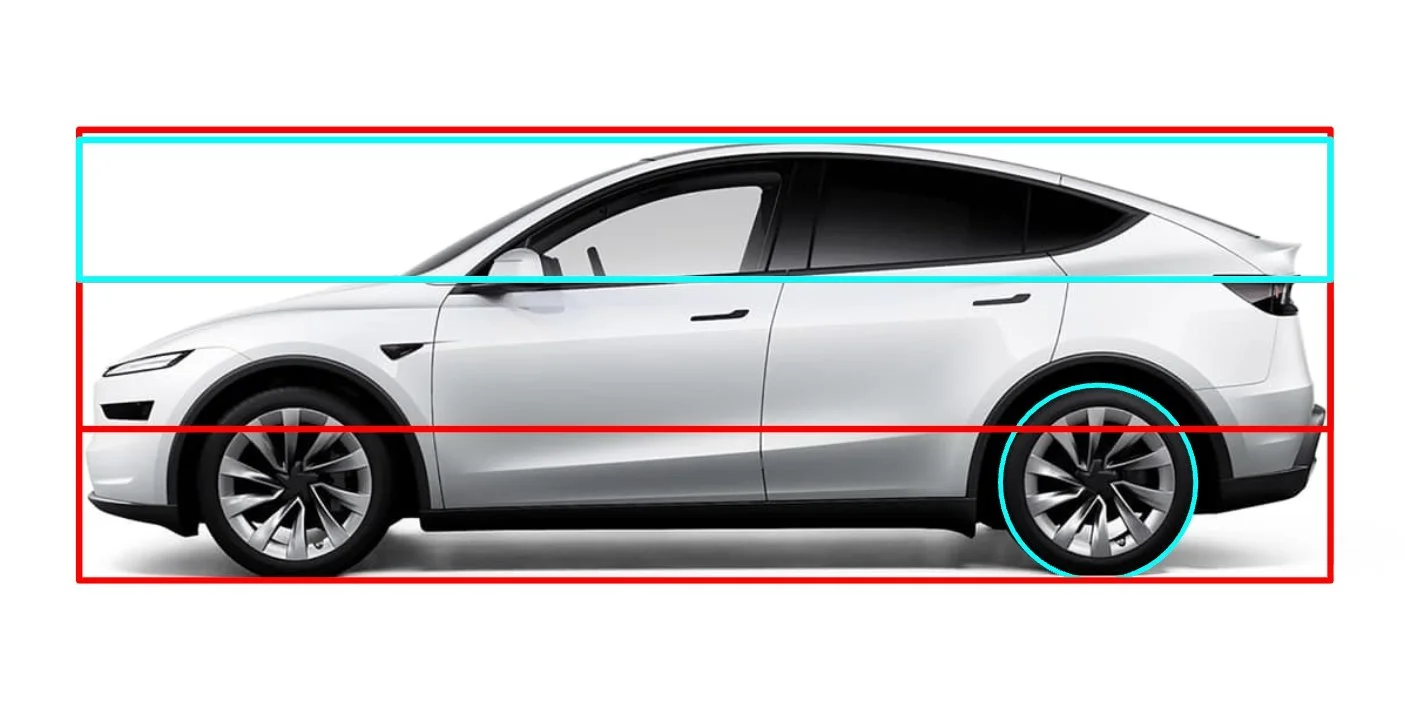

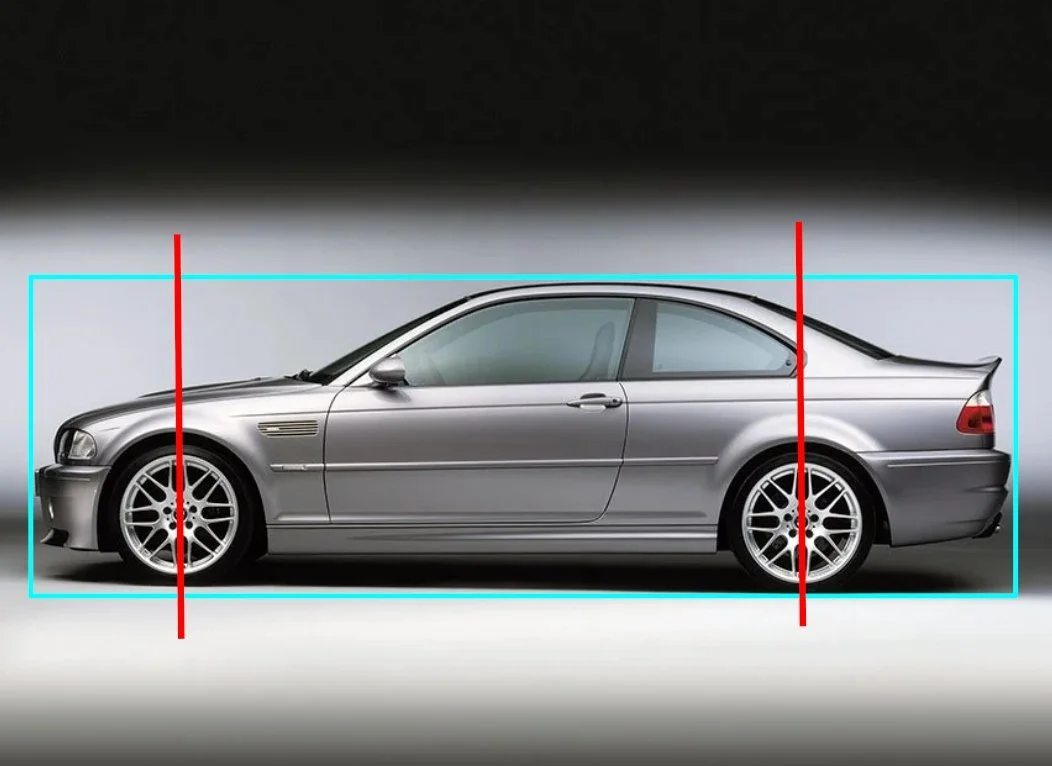

2) Pillars vs. Axles: where the cabin actually sits

A classic proportion rule: the A-pillar (pillars support the roof and are named A, B, C starting at the front and moving backward) should point straight at the front axle center; the C-pillar should start over the rear axle. It puts the cabin between the wheels and communicates rear-drive balance.

E46 M3: textbook. The A-pillar makes a B-line for the axel giving a long dash-to-axle gives a premium nose; C-pillar kicks off over the rear axle so the coupe’s mass sits inside the wheelbase. Your eye reads “front-mid engine, agile, ready.”

Model Y: modern EV packaging + pedestrian-impact geometry push the A-pillar forward of the axle and the C-pillar behind the rear axle. The cabin overshoots at both ends, so the car looks like it’s wearing its body outside the wheelbase box. That alone makes it feel bloated, even though some raw dimensions are similar.

The M3’s lines meet the axles; the Y’s don’t. Once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

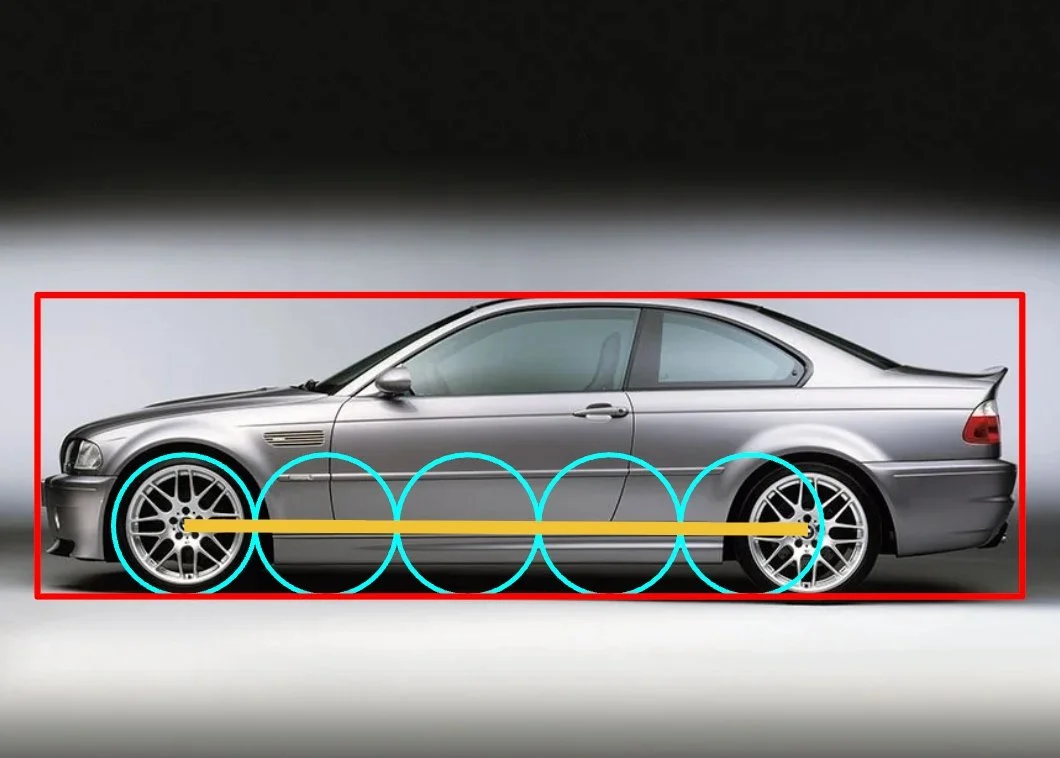

3) Wheelbase to Length: the stance number that can fool you

Here’s the twist: the ratio is surprisingly close.

E46 M3: 2,731 mm wheelbase / 4,492 mm length → 60.8%

Model Y: 2,890 mm wheelbase / 4,794 mm length → 60.3%

On paper, both stake out a “sporty” stance. So why does the Y still have that bloat? Because stance alone isn’t destiny. The pillar placement and extra height undo the benefit, pushing visual mass outside the box that the wheelbase creates.

4) Greenhouse vs. Body: air vs bunker

Specs don’t publish greenhouse height, but you can see it (or measure it in a drawing). The E46 runs a lower beltline with taller glass, roughly in the 35–42% greenhouse band typical of sports cars. The Y has a higher beltline and thicker sills (battery floor), so you get more body, less glass. Tall body sides signal weight and reduce the sense of agility; the cabin feels bunker-ish compared to the BMW’s airy coupe vibe.

5) Overhangs: the illusion of movement

When cars have a larger rear overhang they help to create an illusion of movement. Numbers say both cars are rear-biased, again the M3 has a more rearward stance, but the overhangs are closer than I would have thought:

E46 M3: length ~4492 mm; front ~774 mm (17.2%), rear ~987 mm (22.0%)

Model Y: length ~4790 mm; front ~889 mm (18.6%), rear ~1,011 mm (21.1%)

Yet photos tell a different story. Why? Three reasons:

Height magnifies nose length. A taller hood plane sits closer to your eye level, so the same absolute overhang looks longer.

Surfacing. The Y’s smooth, low-contrast forms don’t break up volume; the M3’s sharper shut lines and shoulder crease visually “cut” length.

Camera angle. Most marketing images are shot slightly above wheel center. On a tall car, that exaggerates the front “shelf.”

So yes, the Y’s front overhang is numerically longer, but the perceived gap is larger still because the nose is high and simple. The M3’s lower hood and crisp lead-edge make the front look shorter than the ruler says.

Why the Tesla looks like an overwrought running shoe

Put the cues together and the metaphor makes sense:

Foam, not bone. Minimal feature lines and big radii create soft transitions with little shadow; it’s the visual language of foam midsole, not taut musculature.

Stack height. Extra overall height, high cowl, and thick sills = a tall “stack.” Even big wheels can’t shrink that.

Cab-forward last. A-pillar ahead of the axle and a long front overhang give the sneaker “toe spring” shape—great for packaging, not for grace.

Beltline bulk. Less glass, more slab makes every surface feel weight-bearing.

The Model Y was designed to maximize space and battery storage. The E46 is the inverse: designed around human scale and mechanical balance, it keeps mass between the wheels, lowers the visual center of gravity, and uses line work to articulate muscle. You don’t need to know the numbers to feel the difference, but the numbers explain why you feel it.

A simple checklist to try at home

Height ÷ Wheel Diameter: aim ~2.1–2.4× for sporty, 2.6–3.0× for crossover.

Pillars vs. Axles: A-pillar pointing to the front axle; C-pillar over rear axle.

Wheelbase ÷ Length: a good stance is ~58–63%; confirm it isn’t undone by tall height or wayward pillars.

Glass vs. Body: more greenhouse reads lighter and more agile.

Overhang reality check: compare the photo impression with the numbers; height and surfacing can lie.

If a car passes three out of five, it will likely “look right” to you on the street. If it fails the pillar test and the height-to-wheel test, your eye will call it bloated, no matter how quick the spec sheet says it is.